Life in an advertising agency — the starting point for this book — has for decades been the kind of business that gives the people who work in it nightmares. That goes most especially for the people who actually write and design the ads.

Your survival depends on how people judge your work, and objective judgments are difficult. Is that TV spot you wrote brilliant, mediocre, or just plain stupid? To some extent it depends on what your boss thinks. And what your boss thinks of your work may depend first on what your boss thinks of you.

For example, I once had a hostile boss who belittled a piece of advertising I had done. He didn’t like copywriters who were older than he was, and I was ten years older. I had to go around him to sell an ad to my to one of the agency’s clients. I was initially rewarded for my efforts with scowls, abusive language, a less-than-sterling job rating, and no raise.

Then the work I had sneaked past my my boss won a major advertising industry award. Since he had “creative directed” the work (by telling me it was lousy and that I was a hack for doing it), he was entitled to share the award with me. Guess what. When we got up to the stage, my boss literally straight-armed me to grab his silver trinket and make an acceptance speech before I could accept mine.

The short, uptight

life expectancy of ad people

Even if they’re very good at what they do, advertising people have short career life expectancies. There are always exceptions, of course, but if you’re not the head of your department by age 45, or CEO by 50, your career probably will find itself on a steep downhill trajectory.

There aren’t many creative people who last long past age 50 at most advertising agencies, much less the traditional retirement age of 65. As Piet Verbeck, one of the great creative directors of the 1970s and 1980s, and still writing ads today, once thundered in an industry publication, “The company cafeterias at most advertising agencies look like the Student Union.”

Since the endangered ad makers are often still highly productive when someone decides it’s time for them to go, new and usually younger bosses tend avoid firing them directly by playing mind games or worse to make them quit.

These have included moving a mid-level supervisor from relatively nice office space into the equivalent of a broom closet. Or badmouthing the employee at every opportunity. Or simply failing to invite the employee to critical meetings and briefings.

Consequently, middle-aged advertising people, often still with a child or two in college and a mortgage that isn’t quite paid off tend to suffer panic attacks and nightmares.

Life in a cardboard box

I once had my own recurring advertising nightmare. In it, I slept in a corrugated refrigerator carton in front of Bloomingdales, the Manhattan department store. It was always during the iciest, windiest day in February. Fear of homelessness made a kind of sense. Why the dreams involved Bloomingdales is beyond me, but I woke up trembling more than once.

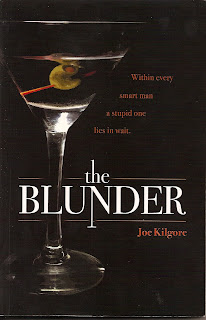

So I think every seasoned advertising copywriter and art director will suffer a flash of recognition from the first sentence of Chicago copywriter and creative director Joe Kilgore’s book, “The Blunder.”

“Brice Lanning had become a relic,” it begins. And from there the nightmare grows, involving a much younger boss who takes away Lanning’s most important account, followed a drunken binge, an equally drunken attempt at sabotage, and a fast downhill slide into homelessness.

Shades of Steinbeck?

I don’t want to reveal too much more of the story, but I will tell you that Kilgore’s homeless character ends up on a long odyssey that takes him from sleeping on a dock on the Chicago River to the Southwest. (Kilgore grew up and spent his early career in Texas before moving to Chicago.) Somehow, the plot brought to mind the kind of agony and misery in America that I last saw explored in John Steinbeck’s book, The Grapes of Wrath, about migrant farm workers during the last depression.

And that’s what suddenly makes “The Blunder” a novel not just for advertising people, but for everyone in this drowning economy. With banks failing, unemployment growing, George Bush all but hiding out in the White House, and John McCain’s campaign desperately trying to change the subject, the middle class suddenly is grappling with survival issues. Or had better start thinking about it.

The Blunder might be one place to begin, while you still have the $14.95 to pay for it.

Monday, October 06, 2008

Suddenly, the U.S. economy makes “The Blunder” a novel for all of us

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

Dear Crank -

I'm too lazy to do a Google, but do you recall a movie with Dudley Moore as a burned out ad man who goes to a mental hospital and ends up employing the clients as writers? I plan to look at The Blundere, but all in all I liked his concept better.

Geff,

I don't remember the movie, but there's nothing surprising about it.

• Some clients stand back and let their ad agencies do the work but...

• Some clients want to do the ads for them. We call them, "lousy clients."

• Other clients simply mutter, "I could have done a better ad than that myself. I would have, too, but I just didn't have the time.

Those clients are also called "lousy clients."

Yours crankily,

The New York Crank

Post a Comment